The last five years of Magic have been remarkable for the dramatic changes they’ve brought to the game, the ways that it’s played, and the way that it is managed by Wizards of the Coast. Here are a few highlights that are particularly relevant for the discussion to follow:

- Between 2017 and 2020, Wizards of the Coast banned fifteen cards in Standard across nine sets over three years, which was more than it had banned in Standard in the previous twenty.

- In late 2019/early 2020, the Pioneer format was created. In August of the same year, combo was axed from the format in a ban of four cards: Inverter of Truth, Kethis of the Hidden Hand, Walking Ballista (from Heliod Combo), and Underworld Breach (from Lotus Field).

- In June 2019, Modern Horizons was released, printing powerful direct-to-Modern staples. In 2021, Modern Horizons 2 was released, completing the effective “rotation” of the once non-rotating format.

- In 2020, as Pioneer seeks to establish itself, in-person play grinds to a halt due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- In 2022, the new Organized Play model rolls out, and the vast majority of all Regional Championship Qualifiers for the first two seasons are Pioneer and Modern.

- After a year of no bans, four more cards are banned from Standard in 2022.

- Lurrus is banned from Pioneer and Modern, and Yorion is banned from Modern.

As in-person competitive Standard play has fallen off a cliff, Pioneer has sought to find its footing, and Modern has permanently changed more dramatically than at any point since its inception in 2011, I’ve heard players both celebrate and lament the fluctuations. Often, the same features that some players criticize in a format are the same that others enjoy. Sometimes, a player contradicts themselves, professing to love a feature in one format, but hate it in another.

Through all the turmoil of Magic’s three biggest competitive formats, I’ve found myself wondering what characteristics a “good” format has. I don’t profess to have found the answer, but I hope some of the ideas here might be useful in framing the hard-to-explain feelings that players have toward the game they love so much.

What is “Good?”

“Good” is an ambiguous term when discussing formats because different players assign different values to format features. Here are a couple of the more common things I hear when I ask players what they mean by “good:”

- A large number of archetypes are represented in the metagame.

- A large number of cards are represented in the metagame.

- There is sufficiently large variation in how the average game of a format plays out.

- The player feels they have agency in deckbuilding; they can make meaningful decisions in deck construction that will impact their win rate.

- The player feels they have agency in gameplay; they can make meaningful decisions during games that will impact their win rate.

- Win rates between archetypes are not heavily lopsided.

- A particular archetype that a player enjoys playing has some minimum viability in the format (a player can play “their” deck).

- There is some minimum threshold of interaction between two players in a typical game.

- The metagame changes from week to week/month to month.

- The format has a unique identity that comes from its decks having unique/distinct identities.

- Appropriate answers exist for the most prevalent threats.

- Play/draw does not feel overly important.

- The quality of the manabases is sufficiently good, but not too good.

Obviously, there is a lot to examine here. The huge diversity in characteristics that people do/don’t prioritize in their format enjoyment is one of the reasons that conversations about format health so often result in players talking past each other.

Some of these topics, such as archetype representation, have been discussed at length by others. As such, I’m going to focus my discussion on a few of the less-discussed.

Axes of Interaction

The axes of interaction are the game zones relevant in any given matchup. While a deck may have a preferred axis of interaction, typically the one on which it wins, it can be forced to interact on another when an opposing deck threatens to win via that axis. Any given deck has a set of axes on which it can interact, with varying efficacy, and the collection of decks in a metagame lead to an emergent set of axes which are relevant in a format. Focusing on Modern, Pioneer, and Standard, the major axes of interaction include: combat, battlefield, graveyard, stack, and hand.

Similar to how midrange, combo, and control have blurry edges, and players may disagree on where the lines are, others may divide up axes of interaction differently from myself. The reason, for example, that I distinguish between combat and battlefield is because there are decks that care about creatures on the battlefield, but do not really need combat to win (Creativity). Under the battlefield label, I’m focusing on creatures – I would consider Enchantress to have the axis of interaction of enchantments, or perhaps non-creature permanents, since artifacts and enchantments are conveniently lumped together.

The axis of interaction of most Limited formats is combat. The vast majority of all Limited decks are built to win through combat, and often the most meaningful decisions of the game occur during combat.

Standard is similar. Usually, combat matters. While decks certainly have the tools to interact on other axes (Make Disappear, Duress, Invoke Justice), Standard is still centered around combat. This centering of a format around one axis allows for a variety of archetypes to exist. Aggro decks can take advantage of being the very best at leveraging the relevant axis. Midrange can organize a gameplan in which combat is still important, but by diversifying its axes of interaction, it can gain an edge against other archetypes which are weaker to interaction on those other axes. And if everyone is agreeing that they will try to win games by attacking with creatures and killing creatures, then semi-creatureless control decks can exist by targeting the battlefield as the axis which needs to be controlled.

Conveniently, this helps to give a nice definition to the oft-used term “linear;” a linear deck is a deck that seeks to maximize a single axis of interaction at the expense of others.

The central question is how axes of interaction contribute to “good” or “bad” formats. Let’s consider some examples.

Standard – Alrund’s Epiphany

While it eventually ate a ban, UR Control with Alrund’s Epiphany dominated Standard in early 2022. The format eventually devolved into UR Epiphany decks and super-aggro Mono-W hite decks. What can we learn about why this happened?

The axis of interaction of UR Epiphany was the stack. The stack is perhaps the most dangerous game zone to make central to a format as only a single color has the ability to interact on that axis (Blue). Typically, the importance of the stack is lessened by spells also being able to be hit in the hand by Black, or answered upon resolution by any color. Epiphany was unique in that its Foretell ability (an upside which bizarrely lowered its cost) insulated it from hand disruption. Further, because it was an extra turn spell, the effect cannot be “answered” upon resolution. The opponent is getting an extra turn, and that’s that.

Epiphany centralized the stack as the major axis of interaction in Standard, and because no other decks could interact on that axis, they were forced to interact on other axes, such as combat. But this meant that UR Epiphany could easily be built to answer the combat axis (which it had amazing tools to do) and win via the stack axis (which nobody else could stop). Normally, a deck like Epiphany could be attacked by a midrange deck like present-day Grixis or Esper Midrange – a deck that can attack the hand, counter key spells, apply pressure, and shut off the graveyard as a secondary axis. But Epiphany’s ability to hide itself in the exile zone, and the combination of Galvanic Iteration and Unexpected Windfall (further stack-based threats) meant that Epiphany couldn’t really be attacked and could accumulate absurd advantage via its stack-based gameplay.

This leads us into another big idea: threats and answers. Threats and answers come up in discussion a lot, and lopsided gameplay like Epiphany Standard occurs when powerful threats exist on one axis (the stack), but powerful answers are on another (the battlefield). Sure, there were also powerful board-based threats, but they all had answers! The stack was unopposed. This is a recipe for polarizing the format into two ends, one stack-based and one combat-based.

Pioneer Lotus Field

Let’s contrast UR Epiphany Standard with Pioneer Lotus Field. Lotus has proven time and time again that it’s a powerful deck, consistently putting up results in major tournaments. But it is far from being a dominant, format-warping force in the Pioneer metagame.

Lotus is similar to Epiphany: it builds a fast mana advantage that can’t really be interacted with, uses the stack as its primary axis of interaction, and uses the graveyard as a secondary axis of interaction. If it “does the thing,” it typically wins in the same turn, but can also do silly over-the-top things like fetching and casting an Ugin if it fails to go off, or casting Zacama post-board.

Why isn’t Lotus as dominant as Epiphany?

First off, the board-based threats are better. Monowhite can race Lotus, and even Rakdos can pressure quickly. But the threats also double as stack-based answers. Monowhite has Tomik, Reidane, and Thalia. Rakdos has Graveyard Trespasser. Monogreen Devotion uses Karn to win, but can also use Karn to grab Damping Sphere and slow down Lotus long enough to do this. Spell Queller and Mausoleum Wanderer are both beaters and slow down Lotus.

Second, there exist actual stack- or hand-based answers. Rakdos, one of the strongest and most popular decks in the format, plays four Thoughtseize in the main, and can add Duress and Go Blank post-board. UW Control can play Narset’s Reversal, which is game over against Lotus. Blue decks like Phoenix and UW play Narset, Parter of Veils, which shuts off the ability of Lotus to draw cards. And outside of possibly Narset’s Reversal, all of these answers don’t feel terrible to use up sideboard spots to play, as they all have utility in other matchups. Lotus isn’t the only deck that uses the stack (Phoenix, UW Control) or the hand as an axis of interaction.

Finally, Epiphany could be built as a deck of board-based answers combined with stack-based threats. Lotus can’t. If it tries to play that game, it becomes too slow and its combo becomes too inconsistent, which means that it must dedicate its entire deck to executing the combo, with a few pieces of board interaction fetchable off Mastermind’s Acquisition. It’s forced to play this way because the aggro decks in Pioneer are faster, and because there are other decks that win on non-combat axes. If Lotus stocked up on board removal to fight Monowhite, its hand becomes more fragile to Rakdos, UW has an easier time countering its key spells, and the wrong answers means losing to alternate board-based threats like Greasefang.

Lotus is the only pure stack-based combo deck in Pioneer, but it has not dominated or polarized the format in the same way as Alrund’s Epiphany in Standard. This is because while other decks don’t try to win via the stack, they are able to interact via the stack (or hand). The threats and answers in Pioneer are far better-aligned along the relevant axes than they were in Standard.

Format Identity

“Standard is all midrange.” // “Standard rewards metagaming and tight gameplay/decision-making.”

“Pioneer is boring.” // “Pioneer rewards knowing matchups and sideboarding well.”

“Modern just kills you randomly with dumb stuff.” // “Modern rewards knowing your deck well.”

The types of complaints and praise I hear for Standard, Pioneer, and Modern are meaningfully different, which suggest there are real, structural differences among the formats. Consider the below metagame snapshots:

Pay attention to the names of the decks. In the Standard metagame, you see a flood of labels that look like [Colors] [Archetype], with Midrange, Control, Aggro, and Tempo, with only Soldiers breaking the mold.

In Modern, you have the exact opposite. The only time [Colors] [Archetype] appears is Rakdos Midrange (and though it’s called Murktide, it’s a pretty traditional UR Tempo deck). Every other deck is a unique animal. Hammer, Creativity, Rhinos, Amulet, Breach, Yawgmoth… the list goes on and on. Unique decks that don’t fit cleanly into an archetype. They all do something that no other deck in Magic really does – which is impressive! An entire format consisting mostly of unique decks is remarkable.

Modern has a stronger identity because its decks are more unique. Its decks can afford to be more unique, leveraging multiple axes of interaction, because the answers also span the full breadth of axes of interaction. Standard’s reputation as “Creatures: the Format” is because its small card pool doesn’t often permit unique decks to emerge; it’s too risky. Saheeli/Felidar showed just how poorly equipped Standard is to handle even a sorcery-speed, expensive, creature-based combo. It’s not impossible for unique decks to emerge, of course; UR Emerge, UW Panharmonicon, and Temur Ascendancy Combo are all examples of success stories. However, it’s unrealistic given the narrow answers to expect Standard to consistently have a significant proportion of its archetypes stray from the aggro/midrange/control/tempo/ramp archetypes.

In Pioneer, you have something between the two. Midrange, Control, and creature-based Aggro fill the top tier, but you also have Monogreen Devotion, Lotus Field, Phoenix, Greasefang, and Enigmatic Incarnation. As more “cool things” get printed and strategies get refined, we can expect Pioneer to get closer to Modern, and the more unique strategies to improve their standing within the format.

While this is certainly not the only difference among the three formats, whether you love/hate some combination of the three might suggest how highly you value format identity. There’s overlap here with whether or not you value getting to play “your deck” in a format. If “your deck” is actually an archetype, you’re likely more amenable to playing Standard. But if “your deck” is a particular, quirky strategy that you enjoy learning the ins and outs of, such as Hammer, then Standard is probably not your favorite format. If you don’t care either way, then that won’t be a factor in your format preferences. This should give some hints as to whether you value “format archetype uniqueness” (or lack thereof) to be an important feature of a “good” format.

Stability vs. Rotation

Back in the pre-Modern Horizons days, one of Modern’s selling points was that it didn’t rotate. You bought a deck, mastered it, and you could play it forever. Would it get a bit better or worse? Sure. Would a new card occasionally get printed that you’d need to pick up? Sure. Would new decks appear out of the blue (Amulet) or when a new card was printed (Colossus Hammer)? Absolutely.

But through it all, you could play Your DeckTM.

Were there complaints every time a new set was printed that it didn’t impact Modern enough? Of course. Were there also complaints when sets (*cough* Oath of the Gatewatch *cough*) single-handedly turned Modern on its head? Obviously.

And then Modern Horizons and Modern Horizons II essentially rotated Modern. While some decks (Tron, Burn) survived mostly intact, the rest of the format changed dramatically. And when this happened there were a lot of complaints. Many Modern players felt like Wizards had violated the promise of the format by rendering irrelevant the vast majority of the card pool.

But then, a year later, many Modern players are complaining that Modern is too static. “It’s been Ragavan vs. Hammer vs. Cascade forever!” they moan, with the rise of Creativity and Breach not enough to satiate their eternal hunger for upheaval.

It’s easy to hear complaints from Modern Players and forget that Modern Players are actually a diverse group of gamers who value different things in their format. When anything happens, the loudest voices are usually those who are upset. Thus, the “stable Modern” vs. “rotating Modern” debate doesn’t expose a hypocrisy, but highlights a diversity of the playerbase.

Players who enjoy frequent changes are likely going to love additional Modern Horizons expansions. New decks, new toys, an exciting time to explore. Players who want to master their deck and play it forever, or master the metagame, or who appreciate a slower, more gradual/natural evolution of their formats will not appreciate additional MH expansions.

Of course, there are other reasons why a player may feel the way they do. Perhaps they like fluctuation, but Modern was their implicitly-promised-by-Wizards-to-never-change format, and they didn’t appreciate having that turned on its head. Nonetheless, how you feel about Modern may give some further insight into whether you value stability or frequent, fast evolution as a feature of a “good” format.

Combo Bans in Pioneer

When Wizards bans cards, whether or not players agree with them, they believe that banning those cards will lead to a better format. As such, this gives us some evidence as to what WotC considers to be bad formats. Let’s take a look at some case studies.

Inverter of Truth/Walking Ballista/Underworld Breach/Kethis, the Hidden Hand

Wizards brought down the banhammer on all four of the major combo decks in Pioneer. Their announcement cited decreases in player participation and enjoyment of the format. They specifically mentioned that no win rates were unreasonable, yet players were not having fun, and that was the reason they were banning combo out of the format. This raises the question: why did players consider this to be a “bad” format?

In this case, I do wonder whether if only one of these decks had existed, rather than four (though only the first three were widely played; Kethis was rather fringe), players would have disliked the format as much. Let’s look at them one at a time:

Inverter: This was a combo-control deck where most of the combo cards (Inverter and Thassa’s Oracle) were heinous. Oracle is a terrible card, and while Inverter could sometimes beat down for a kill, or set up tricky double-inverter wins, you certainly couldn’t just cast it willy-nilly, leaving it to take up space in your hand. Its win rate on MTGO was famously 49%. While the combo itself used a super weird and unique axis of interaction by caring about its library size, graveyard size, and resolving a creature, the gameplay was focused around controlling the opponent’s hand and board. In a format where Thoughtseize was already one of the best cards, it certainly felt powerful that the combo-control deck had access to a modern-level spell. The games themselves were often interesting (sometimes, like any combo deck, they’d just have it on Turn 4), and led to strange cards like Collective Defiance seeing play. Interestingly, most of the current Narset/Day’s Undoing/Notion Thief UB Control deck also existed at the time, which may have been able to use Day’s to kill post-Inverter, but nobody was playing it.

On a purely axis of interaction front, Inverter doesn’t seem that egregious.

Heliod/Ballista: This combo was egregious. Despite being a board-based, two-creature combo, it was often only possible to answer on the stack. If Ballista came in with more than two counters, which wasn’t tough in conjunction with Idyllic Grange or an ETB lifegain trigger, then the opponent would need multiple removal spells to answer the combo. Additionally, Heliod’s indestructibility and not-being-a-creature much of the time meant that it was immune to much of the format’s removal. Here, the answers were not close to good enough to answer the threat of the combo, particularly when, unlike Inverter, both cards were entirely reasonable on their own, and the deck could play an Angels-esque game of gaining life, growing their creatures, and beating down.

Lotus Breach: This build of Lotus was faster, had more space for interaction, was more resilient, and could deterministically kill once it found Breach and Fae of Wishes to grab Tome Scour. While being more graveyard-based opens it to more interaction, Fae of Wishes allowed it to grab answers from the sideboard against most common graveyard hate. Further, as we’re seeing in Modern, Breach is a really powerful card. I agree with this ban more on the power level argument than on any particular axis of interaction argument.

Kethis: Kethis combo was like a worse, creature-based version of Modern Breach. It needed Kethis in play alongside Diligent Excavator to mill, and Mox Ambers to loop from the graveyard (basically – there were lots of other neat things you could do). This deck relied heavily on its creatures surviving and on its graveyard being untouched, two axes of interaction which most other decks in the format were capable of fighting on. Kethis was also not seeing much play at the time; as such, I would’ve left this one around.

On the axis of interaction front, two of the decks are in clear violation, Inverter is on the line, and Kethis is safe. But there could be another reason for players finding the format unfun, closer to the ideas of format identity.

When Pioneer was announced, old, beloved Standard staples spiked. Deathrite Shaman, Siege Rhino, Jace, Vryn’s Prodigy, the list goes on. People envisioned Pioneer as a “best-of” Standard – and then they played it, and it was anything but. It’s not surprising that players were disillusioned, particularly given that “Standard’s Greatest Hits” had pretty much never included combo (Nexus of Fate was quickly banned).

Of course, other arguments from my initial list that we didn’t discuss in-depth, such as metagame diversity, also likely played a role. Players may be amenable to combo existing in their format, but they don’t want most of the top tier of decks to all be combo. It also likely led to players feeling like they had a lack of agency. They do their best to win, but even if they play perfect, they just die to Breach/Inverter/Heliod on Turn 4. This was a situation where several of the features that players value in a format were tanking, and it’s thus unsurprising that Wizards decided to soft-rotate combo out of Pioneer.

Today, Lotus is still around, and quite good, but I don’t hear players clamoring for its ban. In fact, we’ve since added Greasefang, Phoenix, Devotion, and Ignus (admittedly fringe), which all have combo elements. But the format has become more robust, and none of these decks represent a disproportionate share of the metagame, and the axes on which they interact are more likely to match up with other decks than Heliod/Ballista and Lotus Breach.

Other Case Studies

How you feel about each of the formats below may provide further insight into what you value in a format:

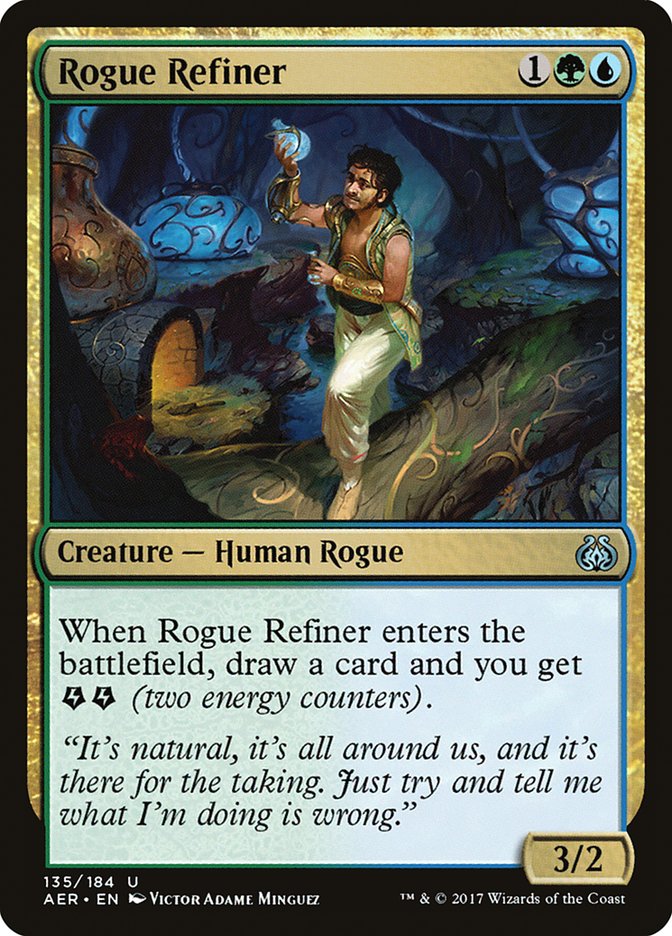

4C Energy Standard: Gameplay was interesting, and there were lots of meaningful choices. Players absolutely had agency. However, Energy was clearly the best deck, so archetype diversity was exceedingly low.

“Turn 3 Modern:” For a period of time, Modern was filled with “ships passing in the night” that killed quickly. There was Infect, Hollow One, Death’s Shadow, Burn, Humans, and Affinity. You did your thing, and your opponent did theirs. Interaction was at an all-time low, there was diversity of micro-archetype, but not macro-archetype, and the metagame was relatively static.

“Today’s MH2 Modern:” The metagame is relatively diverse in terms of macro- and micro-archetypes. Top 8’s regularly include a variety of decks, though Hammer and Murktide have certainly been consistently good, with Breach and Creativity as newer, still-rising stars. But looking at images like the one below, it’s hard not to agree that Modern is diverse on the scale of the decks themselves.

However, on the card level, this is less true. Ragavan, Nimble Pilferer is everywhere, and to a lesser extent, Wrenn and Six, Mishra’s Bauble, and Dragons Rage Channeler and Unholy Heat. Your feelings about today’s Modern format may tease out which type of metagame diversity you value most.

Conclusion

Players want different, often contradictory, things out of their formats. “Good” and “bad” aren’t as objective labels as experience bias would have us believe. There are so many different elements which create the emergent format that we all experience, and being cognizant of these fundamental building blocks can be helpful in learning more about what we, and those around us, like or dislike about Magic’s formats.

Ryan Normandin is a grinder from Boston who has lost at the Pro Tour, in GP & SCG Top 8's, and to 7-year-olds at FNM. Despite being described as "not funny" by his best friend and "the worst Magic player ever" by Twitch chat, he cheerfully decided to blend his lack of talents together to write funny articles about Magic.